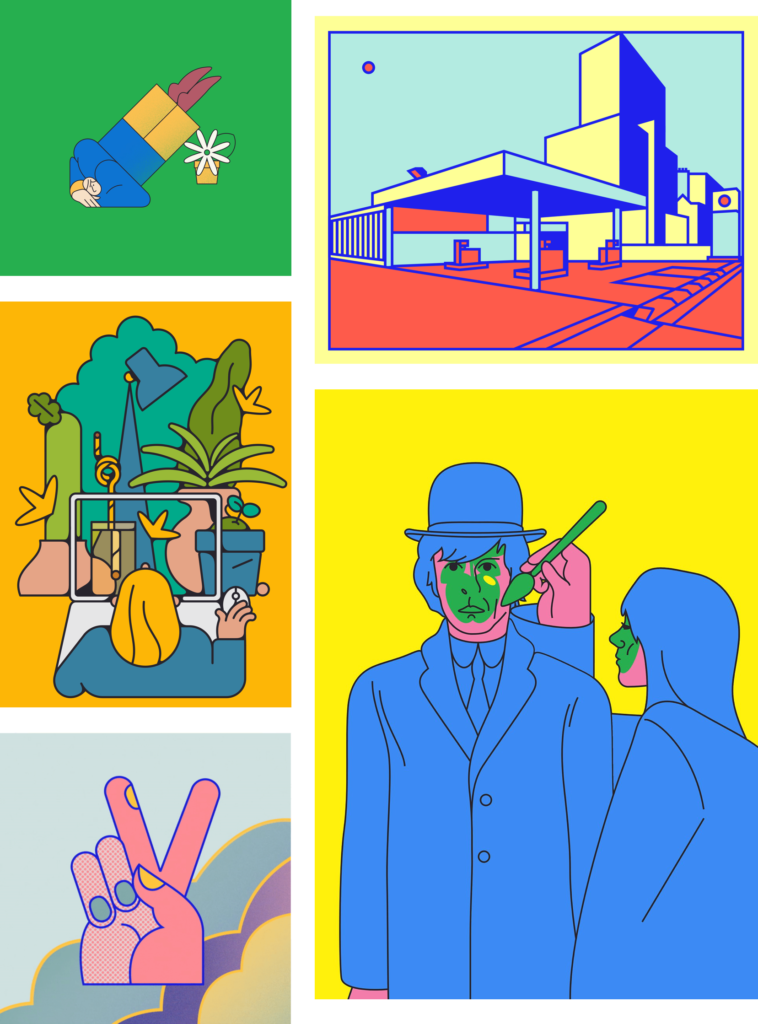

Thomas Hedger is an award winning artist, based in London, whose work captures majestically the energy of our frantic lives and the small, little details we are often too busy to pay attention to. His style is characterised by strong lines, geometric shapes, vector illustrations, pop landscapes, and a combination of vivacious colors and gradients. Thomas’ work is primarily printed and digital, but not only limited to that, as he also experiments with 3D installations and sculpture.

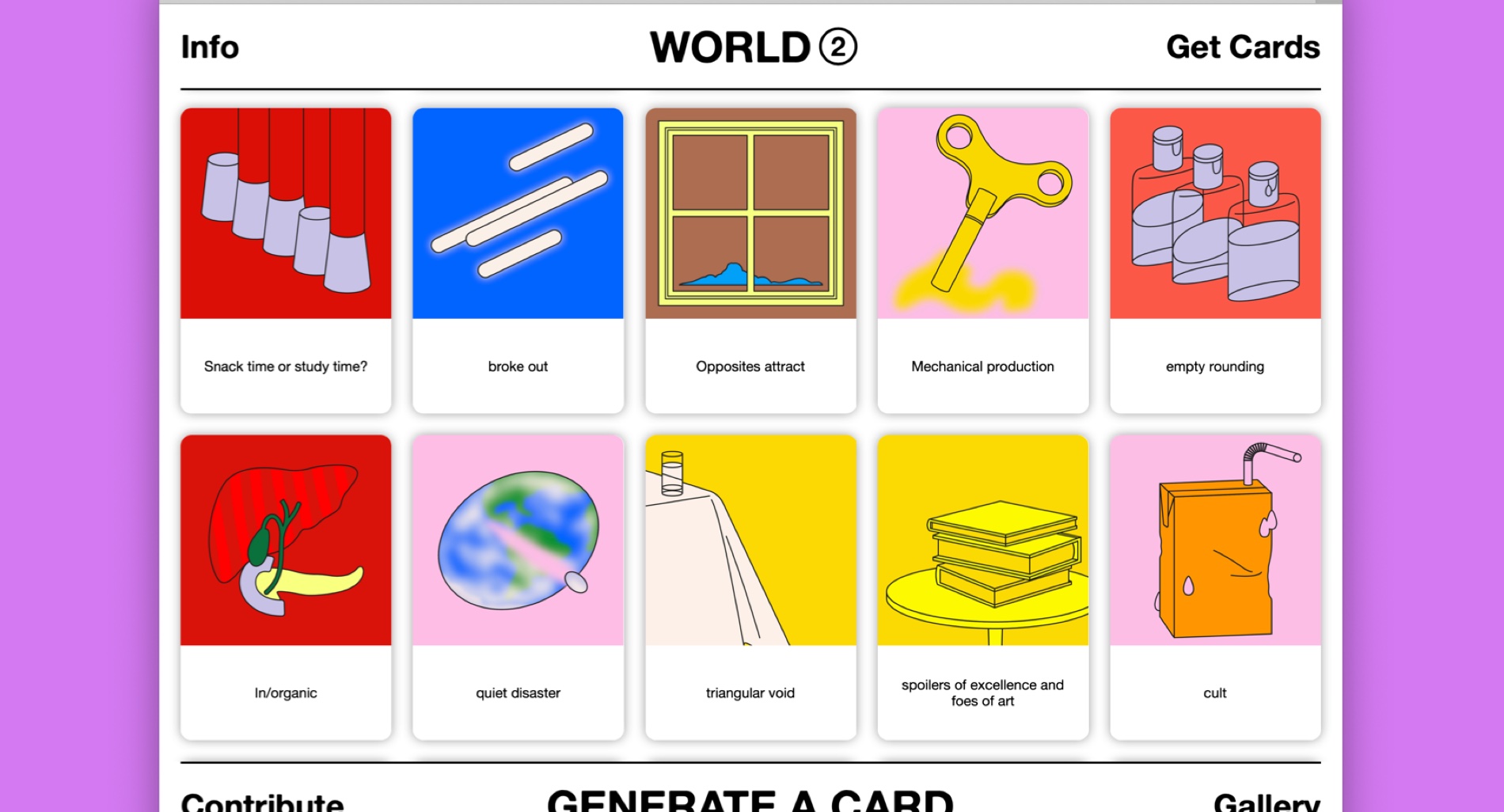

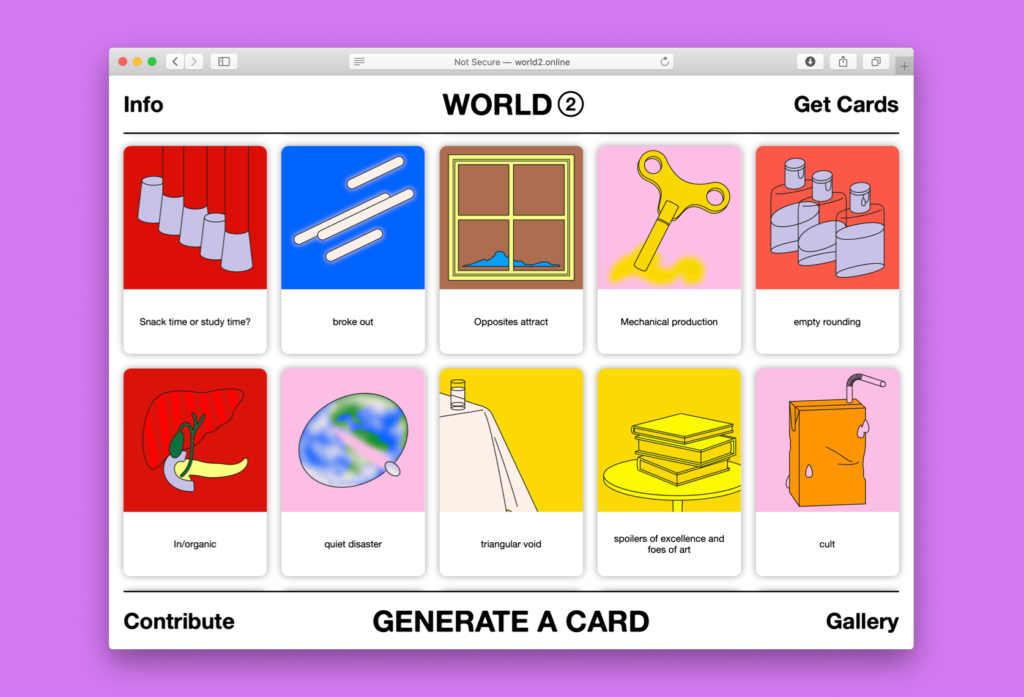

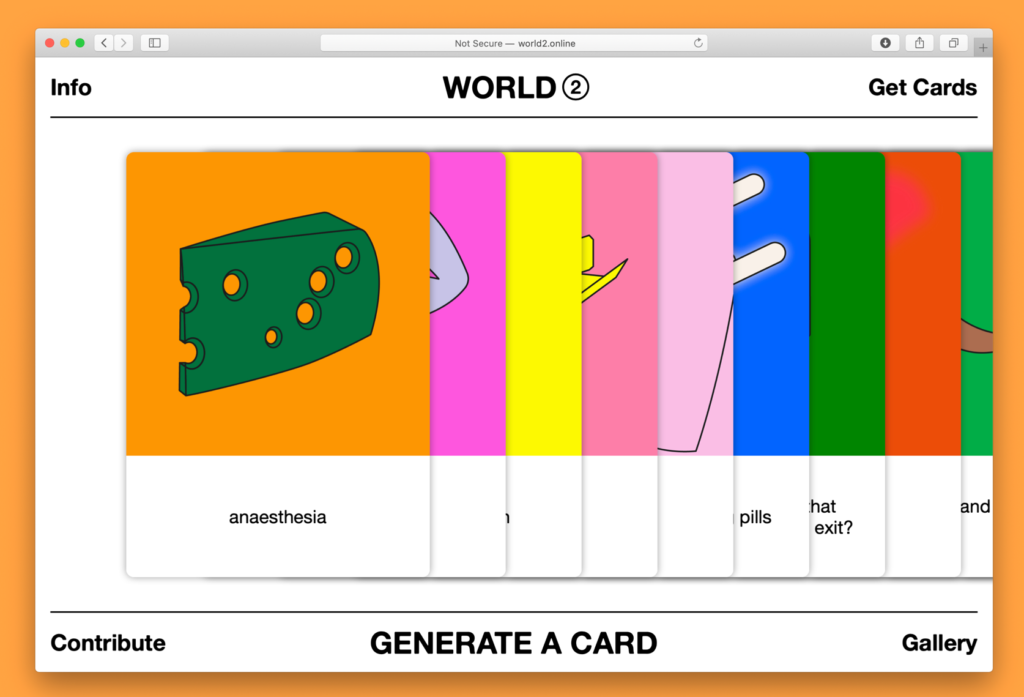

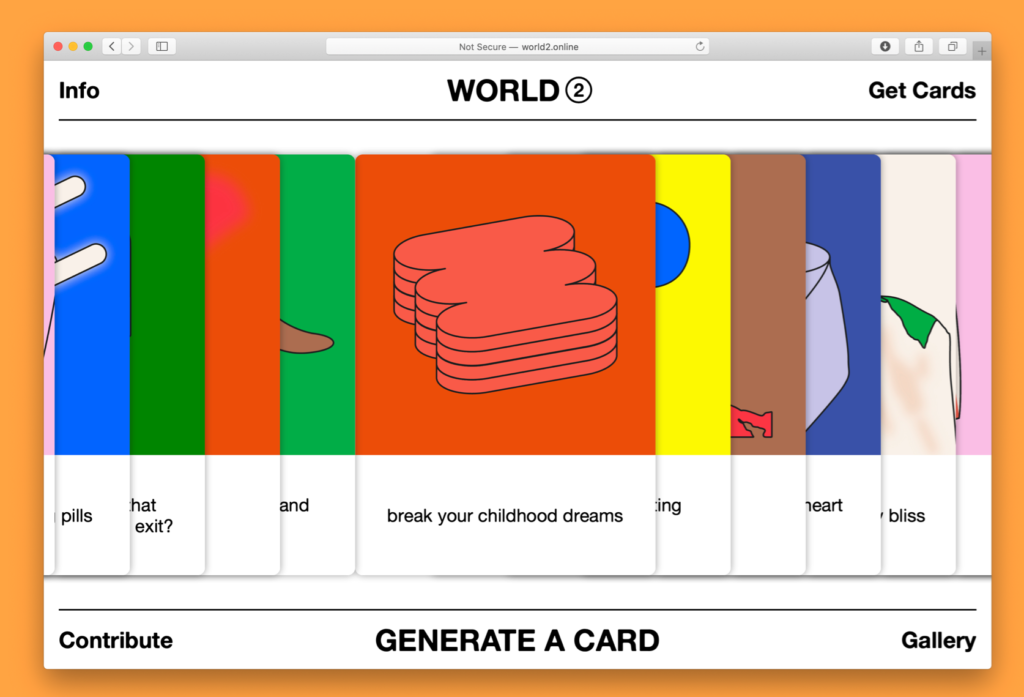

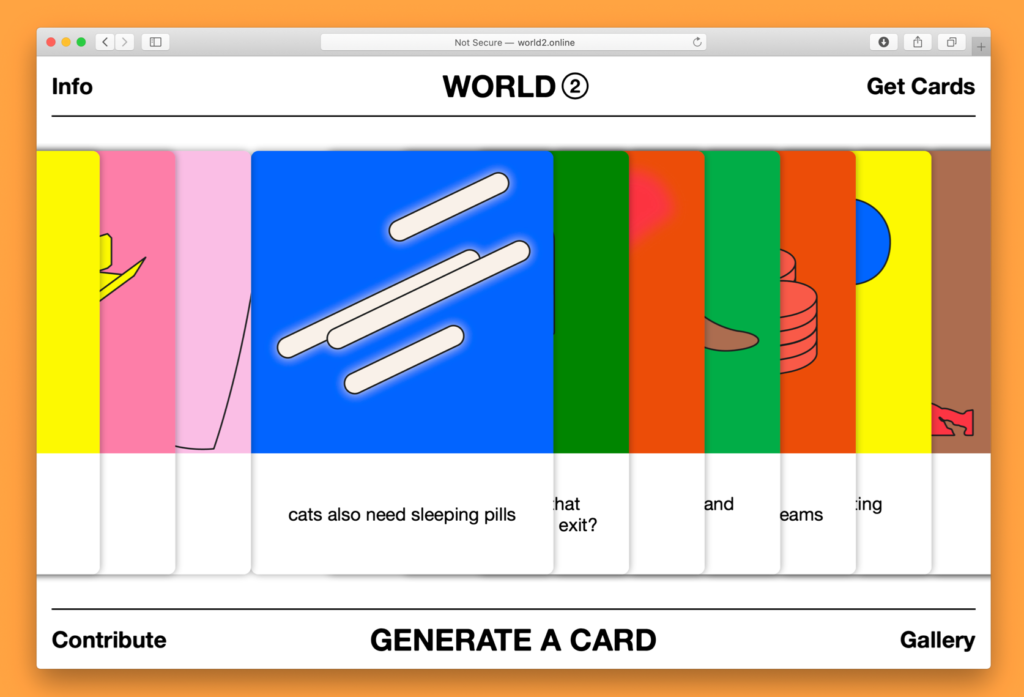

One of his latest projects is World2, a digital space created to prompt the relationship between visuals and language, aiming at exploring new and different narratives through collaborative interaction.

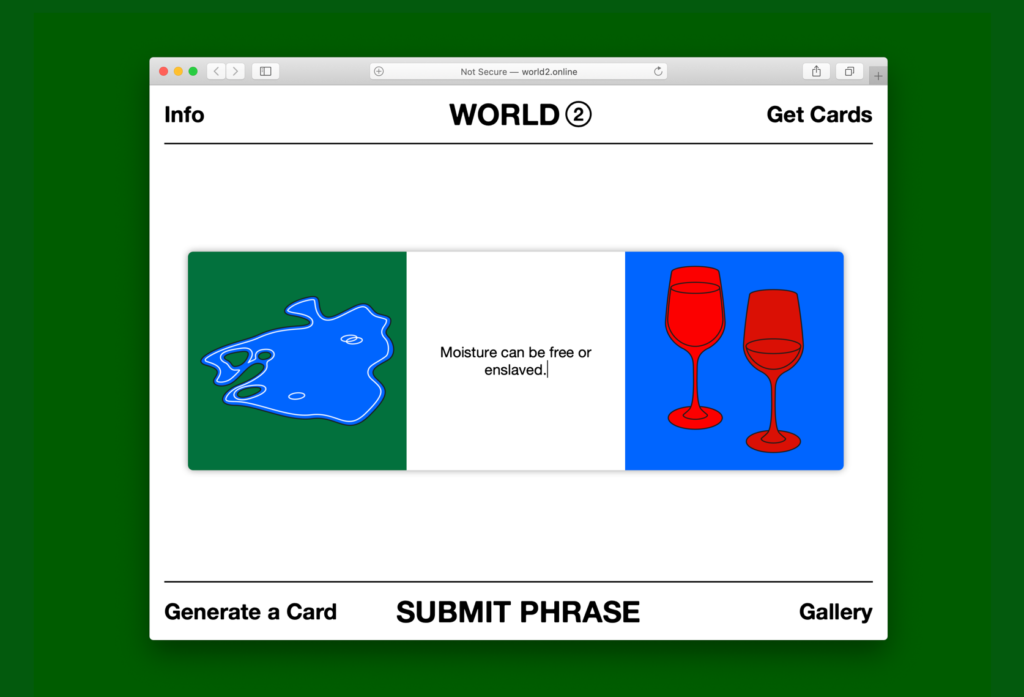

In the website you can generate a card, which is created by a random association between image and text, taken from a predefined dataset. This new narrative can be submitted to the gallery, which acts as a resource for interesting and unique stories. In World2, you can also add a written connection between pairs of images. The text can be anything from a description, thought, or poetry that is read between the images. These texts are then combined with the existing dialogue for others to generate cards from. All the cards on the website can be downloaded.

Thomas will share his knowledge and experience in a talk at Design Matters 20. In the meantime, we interviewed him to learn more about the process involved in the creation of World2, the challenges he faced in building this digital space, and what inspires him to create his amazing artworks.

Can you tell us more about World2? How did you come up with the idea? Why is it called World2?

I want World2 to be an open space for thought and collaboration. In creating conversations between image and text, I’m interested in an image’s ability to obtain partial autonomy to form narratives. World2 is based on Karl Popper’s theory of three worlds: World1, the world of the physical, World2, the world of mental processes, and World3, the world of objective knowledge. With this, I’m looking into audience feedback, and how the interpretations from contributors can transform the image into something more than my intentions, by providing deeper meanings and unusual stories. I’m hoping to show the importance of conversation in image-making, the impact of circulation on an authoritative voice, and how illustration can be used as a language.

What was the purpose of this project?

The website works by randomly pairing an image with a piece of text. The images are a set of prompts, some are easier to identify and some are more ambiguous. I found that this mix was able to offer more stimulating responses than when they were all simple or abstract. The texts have all come from contributors: when contributing to the site you are presented with a pair of random images and invited to write a short text that is discursive, descriptive, detailed or abstract, anything from a thought, phrase or poetry that is read between the images. All these images and texts are then randomly paired when you generate a card, and if there is a pair you like it can be saved to the gallery. The gallery then becomes a space for autonomous and unpredictable stories and conversations. There are over 150 unique images so far, but I am still adding to the site. The more contributions I receive the more inspiration I have for a drawing. I wanted there to be a cycle, image to text, back to an image, and so on, to maintain this circulation and for the World2 website to be an interesting space for people who haven’t contributed yet.

What are some of your favourite contributions?

All of them! Without sounding completely lame, I appreciate that people have taken time out to be engaged in this project for a brief moment and help this research. If I have to pull a theme out though, I’m excited by the ones which connect with my initial research and have a bit of grit — touching upon the qualities of media, sameness and the memetic. This was a space to surprise me, changing how I connect with my work in order to evolve. They work in curious ways when paired with the drawings, lifting them into conversations I could never have simulated. All the contributions are successful in forcing a narrative onto the drawing, creating an odd series of images that somehow connect and speak beyond how I interpreted them. Even though some of these texts are literal, abstract, political, poetic or emotive, they are all relevant; and that inspires me to give this project an afterlife to highlight them.

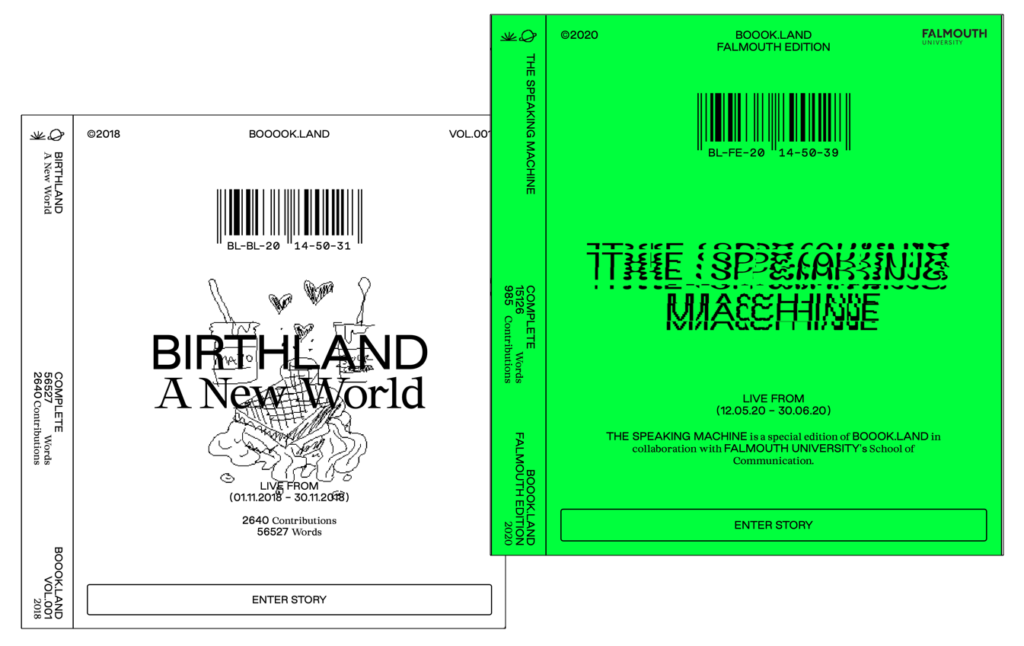

You chose Twomuch.studio to build the website. Why did you choose them specifically?

Twomuch.studio are a really interesting design studio as they’re able to balance design and functionality so well. I’ve been waiting for an excuse to finally do something together, but what made them a studio I wanted to work with is that they have done other collaborative open-source projects like twogether and boook.land — both super interesting projects that rely on contribution and interaction to bring their ideas to life. When I started planning this project for a digital space, I wasn’t too sure about the limitations or possibilities for World2. I have some understanding of how it all works, but it’s good to ask for help sometimes, and it felt right for a project that is all about collaboration to work with a studio that embraces that so intrinsically!

What challenges did you face while working on this project?

In a strange but happy ending sort of way, World2 was built out of challenges. I had intended for my research to come together and take on a more material approach, with interactivity coming from a physicality, like hands on making or drawing together. After COVID-19 and lockdown I couldn’t access the studio or making labs so these material explorations became impossible, and I started to think about this research in a digital space. Being in a position where I had to realign my ideas was good though, the project would never have manifested otherwise and it gave me the time to focus on language, circulation, and authorship more directly. I’m happy it took this direction, I think that reducing those ideas to a simpler form, working with images directly, gave the project some clarity. By stepping back on the narrative storytelling, it was easier to highlight the importance of collaboration and language, which could have potentially been lost. It’s allowed me to connect in different ways that hopefully still enable development in my practice.

In general, where do you find inspiration? Who or what inspires you?

Like most creatives, I have an obsessive love of art. I like looking at it, discovering new work and then going deeper into an artist’s older works. With my own practice, I’m inspired by language and ambience. I’m trying to locate ways of storytelling that are more immersive, less determined and rely on conversations to challenge my own authoritative voice. The treatment of colour and spatial voids comes down to a hunt for mood. I want my work to capture emotion, not from objects or people but from the feelings that can’t be explained. For World2, I surrounded myself with artists like Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, Hamish Fulton, Martin Creed… My ongoing list is made up of artists who I feel use language at the core of their image-making, something I don’t want to lose sight of in my own process.

Are you experimenting with anything in particular these days?

Nothing that I can successfully share! With World2, I eventually want to gather all the submissions together into a physical form as a way to conclude this part of my research. Meanwhile, I’ve been playing with etching-at-home and other curious print-making techniques, and am still in progress to produce anything to be proud of yet, but I think all these little experiments are what keeps me interested in drawing and making. Who knows when I’ll hit upon something that feels just right which will help push my work in a new direction? For now, I’ll just keep drawing.

More by Thomas