Design Matters met with Eriol to discuss how the Covid-19 crisis is being handled from a digital point of view, designers’ responsibility towards humanitarian issues, and the technology involved in crisis response.

What is it like working as a designer for humanitarian causes?

Doing design-related humanitarian work involves a huge amount of emotional work that I have personally had to do to really understand how to compassionately receive trauma from other people. I question what my role is as a designer in relation to the individuals who talk to me about their experiences. I think one of the best things I have done as a designer who works for humanitarian causes is to do the doing as well as the conceptualising, thinking and building. It’s hard because I’m constantly a certain percentage of designer and technologist, and a certain percentage of helping repair this person’s home, or that devastation or disaster. Anyone who is ever interested in working as a designer within the humanitarian space — regardless of what that space is — I always say, think of how you can get involved and respond to that space outside of the design context.

How do you think that the current crisis is being handled by nations and is there anywhere specifically that you really support in their approach?

There are interesting topics that are now being given considerable time. It’s always super dangerous for somebody who’s a national of one country, i.e. the UK, to comment and say this country is doing it right. I’ve had that trap before around diversity and inclusion questions, and it’s difficult to answer unless you are within that space. I guess it comes down to what you value. In South Korea where there is invasion into your privacy, there is also the likelihood that you are infecting less people. One thing the UK did amazingly was the mutual aid groups. There are literally hundreds of thousands of groups and communities across the UK dedicated to helping their local people — they do things like check in on the elderly people on your street. This is Ushahidi-related stuff. Communities naturally do this in a crisis. Humans will gravitate towards the things they know best — sometimes that’s Facebook, sometimes that’s a notice board down the end of the street. Whether technology can bridge this gap remains a question.

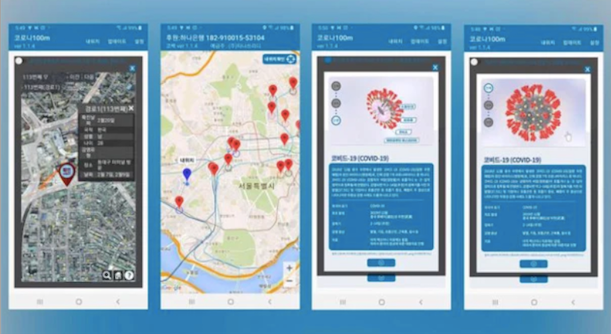

South Korea developed an app called Corona 100m which foreigners have to install on arrival at the airport. It informs you if there are any coronavirus cases within 100m from where you are. As both a designer and as someone who works with humanitarian crisis, what are your thoughts on people’s privacy?

This is a huge topic. I’m connected with some of the folk who are working on technology in Taiwan; I went to an online session from the Taipei Ladies of UX. They were doing video-mapping for people who work in the health services and I contributed a UK perspective. I think one of the things that is interesting about the coronavirus is the coming together of communities — the tech community is one of them. Our instinct is to solve, and I think breaching privacy is that knee-jerk response to solving and doing it without thinking of the consequences.

I’m less nervous about some of the privacy things because I see communities having a considerate approach. Privacy and security topics have been spoken about for a while. There was a push for finger recognition across rural India to give medication to undocumented people. People will give you their fingerprint because they really want their medication, but do they really understand why they are giving their fingerprint? There was also a conversation about facial recognition in Nigeria and Kenya last year. This has been a concern for human rights groups for a long time. There’s some great work being done by the Electronic Frontier Foundation on this.

This privacy concern serves a certain part of the population reasonably well. The majority of countries don’t have things that you are criminalised or socially penalised for doing, so most people are going to be safe. But marginalised populations — like those involved in the Hong Kong protests — are in danger of being recognised when they are asked to download an application. Unless you’re really careful and you know exactly what something is doing when you download it on your phone, you just don’t know where your stuff is going. We’ve seen this with Zoom, and with any internet platform. This can be really harmful to people who could face retaliation like LGBT people who are criminalised — that’s what I really worry about.

There’s a lot happening in the space around trying to teach people who are human rights activists and whistleblow on their government. A lot of good organisations teach how to encrypt files, or where to upload government documents to leak to press. This pandemic shines a light on the need for privacy education.

You have recently been involved in a charitable organisation, Team Rubicon UK, can you tell us about it?

Team Rubicon UK is a branch of an organisation that started in the USA by two ex-military men after the Haiti disaster. When they decided to go to Haiti, Team Rubicon weren’t an organisation at this point, but they managed to mobilise an immense amount of support for communities and taught people how to clean up and make basic repairs. This is how it all started.

What was your role at Team Rubicon?

I’ve done a lot of design research and UX interviews around having different charitable organisations coming in and trying to help. They won’t necessarily communicate very well with each other. When there is a crisis, there is a period when you do a needs assessment. We helped set up the Nightingale hospital in London, a dedicated NHS supermarket, delivered meals to NHS staff, and we’ve also done a lot of tasks involving creating temporary mortuaries. I was trying to triage and manage all the different needs coming in. I’m a techy person and I do techy things, but I also have an understanding of how to manage a crisis.

Usually there is an overwhelming amount of information and not enough people to analyse the information as its happening. One of the big gaps generally in crisis when it’s a pandemic like Covid-19 is that the critical moments are the weeks, days and hours just before.

There is an absence of data scientists, analysts, and people who make sense of trends. Also, there is huge competition for resources and the need for a judgment call. Should this region get it? Or this one? Or do you split it? Is it first-come-first-serve?

If different charitable organisations aren’t communicating effectively with each other, you may find that two bodies have made the same judgment call. Did you find that Team Rubicon was communicative with other organisations?

There have definitely been cases where a community that has had some kind of natural disaster will have too much water and what they need is another generator to charge their mobile phones. Organisations — especially the big ones — won’t necessarily report that they delivered people water and it wasn’t actually needed. This is understandable in a business context. People forget that non-profits are a kind of flavour of business, they just report different metrics.

In international crises, there is a lot of competition and duplication of resource. You can get into non-profit politics which is super dangerous.

Team Rubicon actually recognise that communication is absolutely critical. They decided that they were only going to help where there were unmet needs. Lets say, a food bank needs people to sort through their warehouse because they’re getting too many deliveries of supermarkets that have closed down. They had to start turning away vans of food because they didn’t have people to take it or the space to store it. If forums, military and other organisations are unable to help, then Team Rubicon are there to say “yes, we will do this.”

You mentioned that both volunteers and veterans help you. Do veterans have particular skills or advantages compared to volunteers?

The military are taught a certain amount of resilience that you don’t get taught as a general civilian. You get taught how to perform under immense pressure — both physical and mental — and how to interact with people all over the world in really intense situations. You tend to have specialised skills; there are medics, engineers and people who can do machinery-based stuff. There’s a certain level of physical fitness that’s required of the military.

Team Rubicon want volunteers who are coming in from a technology perspective or from any kind of under-served sector that has immense value and skill to offer. Also, Team Rubicon provides lots of training for volunteers to deploy all over the UK and then internationally. A lot of civilian-type folks can’t believe that you can volunteer for crisis response.

What does the military approach consist of?

At the very base-level, it’s getting stuff done. You have a mission and you complete that mission. That’s really embedded within Team Rubicon and that comes from this military understanding of you go in, you get this job done, and then you go out. It’s also a very camaraderie approach. A lot of conversations are being had at Team Rubicon now about the sustainability and effect they are having on a community.

I was very surprised within my training for Team Rubicon how often they check in with each other on a really deep level. They do something called a “play of the day.” At the end of every day on an operation, there is an opportunity to say what has affected them, and whether they may benefit from some emotional support — that is what it means being a part of Team Rubicon. When we think of the military, we think of quite stony-faced people, but there is a real emerging culture within the emotional side of things for it to be really important that you check on your comrades, otherwise you won’t get the job done. I think a lot of other industries could learn from them.