Former Design Director at IDEO and past speaker for Design Matters 2017 Karoline K, specialises in visual storytelling, regenerative design, and the circular economy. Karoline is one of the lead creators behind the Circular Design Guide. A guide that is meant to inspire a new mindset towards design and put it into fruition, to help innovators and creators design effective and creative solutions for the circular economy.

Circular Design is about thinking in systems, understanding material flows and using technology to embed feedback mechanisms throughout the design process. It involves getting creative with business models and ultimately plays an active role in designing for a future with everyone in mind. Originally from Denmark, designer and strategist Karoline K is based in London, where she is building a product team at Centre for Homelessness Impact, an organization that’s accelerating the end of systemic homelessness by using evidence to understand what works (and doesn’t work).

Talk to us about pessimism

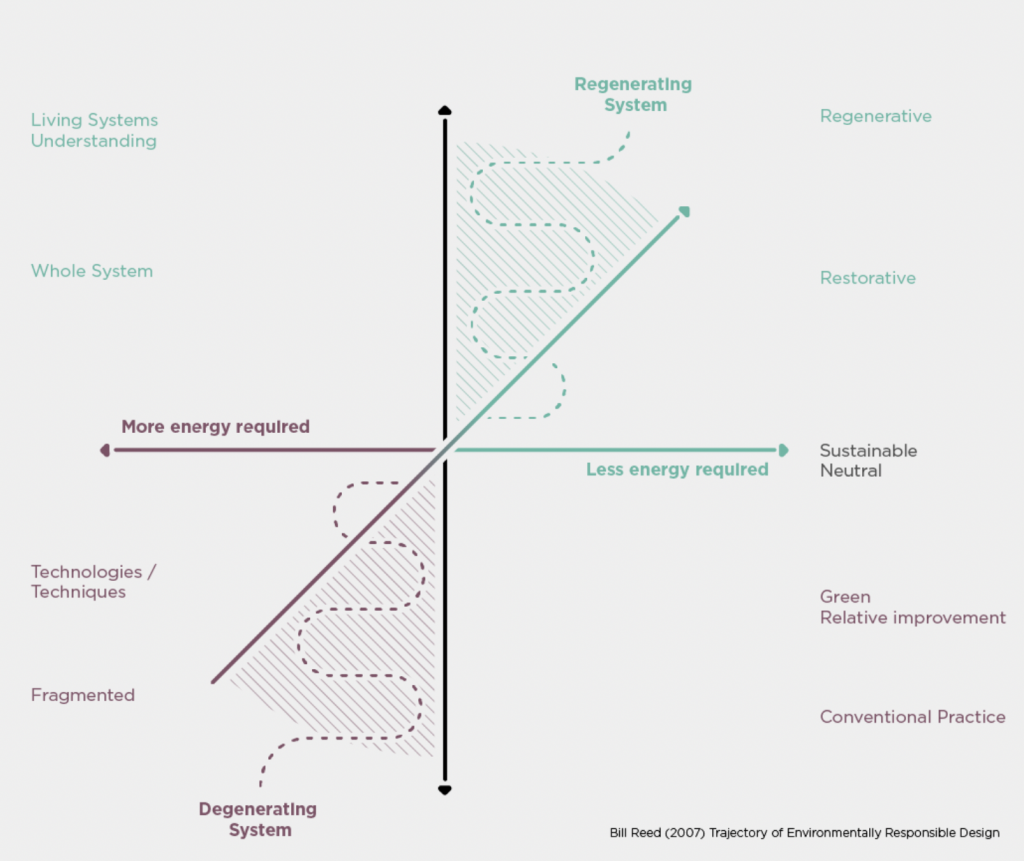

As designers we’re in the business of optimism. We’re trained to be on the lookout for things to improve, and possibilities to imagine. And we really do need that optimism to re-imagine a better future for our planet, to envision new types of abundance and to design systems that are regenerative by design.

Optimism alone won’t take us there, though I think. We also need to sharpen our critical toolkit, and imagine what could go wrong despite our best intentions. That means not just looking at your end of the problem, but factoring in the system and context your design exists within. That could be a natural ecosystem, a structural system of oppression – or a value chain that involves a lot of waste.

It’s not easy, but it helps to compliment your designer-y optimism, with what I like to call proactive pessimism.

Interesting.. And how does it work in practice?

Sometimes it’s simply asking yourself, what might be the unintended consequences of what we’re designing? Could we cause harm to people or the planet further down the line, or even during our design process?

It’s about getting better at thinking about what can go wrong. I think we’re often taught to think about possibilities and solutions. And that’s great. And we need that. As part of your process, it’s worth thinking about all the negative scenarios – a bit like catastrophizing – like, no really, what IS the worst that can happen?

Could we, unintentionally, cause harm to the people that we’re talking to as part of our process? What happens when people are done using the thing we’re designing? What if it gets misused?

Creating intentional time and space to wear critical hats or be Debbie Downers as part of your design process is a good place to start.

You were part of creating the Circular Design Guide, what advice do you have to designers who are just getting started with circularity.

Making the Circular Design Guide was a really incredible experience of bringing together what we know worked well in terms of design and problem solving – I was working at IDEO at the time – and combining that with the vast and deep expertise of good folks at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. We sort of didn’t understand each other’s worlds very well at that time, but shared a belief that design has a role to play in the transition to a circular world. We tried to be quite pragmatic and lower the barrier to engaging with the topic, so most of the tools on there are designed to be used by beginners for sure.

Something I learned early on is that it’s pretty much impossible to create a ‘perfect’ circular solution on your own. It requires a lot of connection and shared goals between all the players and stakeholders who are part of the ecosystem operating within – who’s making the thing, where’s it? How’s it travelling? How’s it getting to people? If you follow the material around on its journey to get in the hands of someone, you’ll realize there’s a lot of people and micro-decisions involved.

The good news is designers are really good at designing and facilitating meetings, as well as painting vivid pictures of what alternative futures could look like if people and organizations held hands a bit more towards shared goals that make our planet better, not worse.

How are you seeing the more traditional, linear approach to design shifting?

I think designers are starting to feel more responsible for what happens to their design out in the world and in its afterlife. Not sure if this is also influenced by the internet and how nothing ever truly disappears.

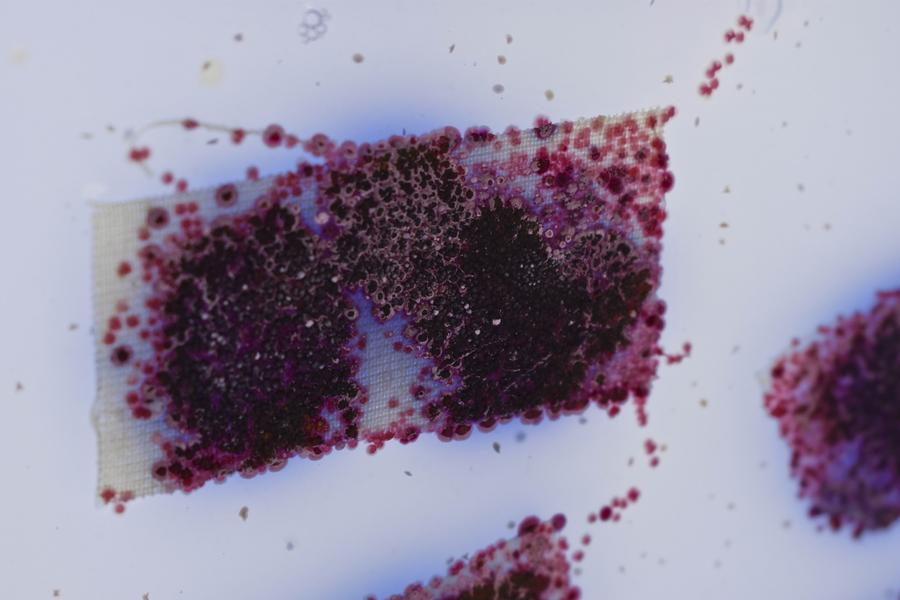

I don’t do a lot of physical product design, but those who do I imagine are more aware of the life of their materials, where it comes from and where it ends up when it’s no longer in use. Some of the material innovation is also incredibly beautiful, I think we’re only seeing the beginning of what will be possible. I love Natsai Audrey Chieza’s work creating fabric patterns using bacteria, and her work to integrate life into the manufacturing of materials.

On the process side, I’m seeing a nice shift away from assuming that a ‘beginners mindset’ is always the most useful. Over the years I’ve definitely embraced naivetë in a way I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing today – where the point zero in a project was my own lack of knowledge, as opposed to starting off by looking at the historical context, including all the people that have worked to solve that very issue before. I’m seeing teams bringing on historians and treating lived experience as crucial expertise needed to do good design. Not sure if this squarely circular design, but it feels more responsible so I think it counts.

What are you reading that you would recommend?

One book that has been really eye opening to me is Emergent Strategy, by Adrienne Maree Brown. It explores our relationship to change and offers kind of a way to look up patterns in the world. She draws a lot on science, but as a science fiction, poetry, and forestry, and has really opened my mind to how important it is to reimagine the world as it could be, not in its current structures like capitalism that don’t serve us or the planet well. I also find her reflections and writing on the pandemic deeply moving.

There’s also so many people experimenting in the circular design space, and I always like seeing what practitioners are up to out in the real world – there’s more than 28K people in this linkedin group we setup when we were just launching the circular design guide, it was almost an afterthought, but I’m really glad it exists.

Back to pessimism, how can design teams think about expanding their process in response to where our world is at?

If you’re leading a design team, think about the rooms you’re creating. Is it a space where people can disagree and where red flags are valued? Can the most junior folks safely speak out? Whose voices are being centred, and who is not in the room? It’s really easy as managers to forget that power dynamics are very real and influence psychological safety. Even if you pride yourself on not having a hierarchy, it most likely exists, so it’s better not to ignore it.

Build time for reflection into your design process, so there’s space to unpack all those ‘what if’s and conversations about unintended consequences. Topics like circularity can also trigger climate anxiety, so keep an eye on your team’s mental health and anticipate that they’ll need time to rest and decompress, and may need to find their sources of energy from outside the project room/zoom.

Any resolutions for 2022?

After spending many hours in the timewarp that was 2020/2021 deep in my screen, I’m really hoping to spend more time in 2022 touching base with the tangible a bit more. DIY and woodworking is top of my list, and saying that out loud might just hold me accountable to actually doing it, so please check back in!