You’ve likely been in a design thinking workshop, or been exposed to one of the thousands of iterations of diagrams depicting this process. Design Thinking is a nearly ubiquitous and invaluable tool, providing a best practice framework for design processes. It’s time now to shift gears, evolve, and serve the needs of a new future. We’re living in an uncertain world and we’re at “the fuzzy front end”, one of the most wonderful and daunting parts of a design process where we don’t know in which direction we’re headed. We are taught to categorize, define, and have clear goals – but the fuzzy front end doesn’t have a goal, it in itself is a destination where we can design from. However, this destination has three inherent problems and design thinking needs to evolve in order to help us solve those problems and design better futures:

1. The user-centric approach individualizes. It designs products for the individual, the solitary user. Such individualization can be seen as part of enlightenment thinking where the modern subject is portrayed as autonomous – separated from the world, making everything else mere materials for the actions and agency of this subject.

2. Seamless interaction is all the rage. Through iterations, prototyping, and testing, design thinking reduces complexity and creates “seamless interaction” wherein something “well-designed is unnoticeable”, and any friction is ironed out to make the experience as smooth and convenient as possible.

3. The design thinking methodology promotes a mirroring of the users’ wants instead of their needs due to the user-centric, best-practice approach. This leads to design for wants and instant gratification. Design becomes a process of designing sleek, frictionless channels for optimizing and perpetuating consumption.

Design thinking needs to adapt to a world of tomorrow and become something that can contribute to the social and ecological transformation so desperately needed for both the planet and humankind. We are looking for a new system of design semiotics: at the same time, a changed practice and a new vocabulary for what is at the heart of design and what design strives to be and do. We need to reframe (to use a design thinking term) our relationship to the world around us and to how we relate to other living creatures and our planet as a whole. For us, design should facilitate meaningfulness, genuine moments of significance, and critical thinking. And this requires friction.

“For us, design should facilitate meaningfulness, genuine moments of significance, and critical thinking. And this requires friction”.

V. Carpenter & H. Lübker

Designing for Meaningfulness

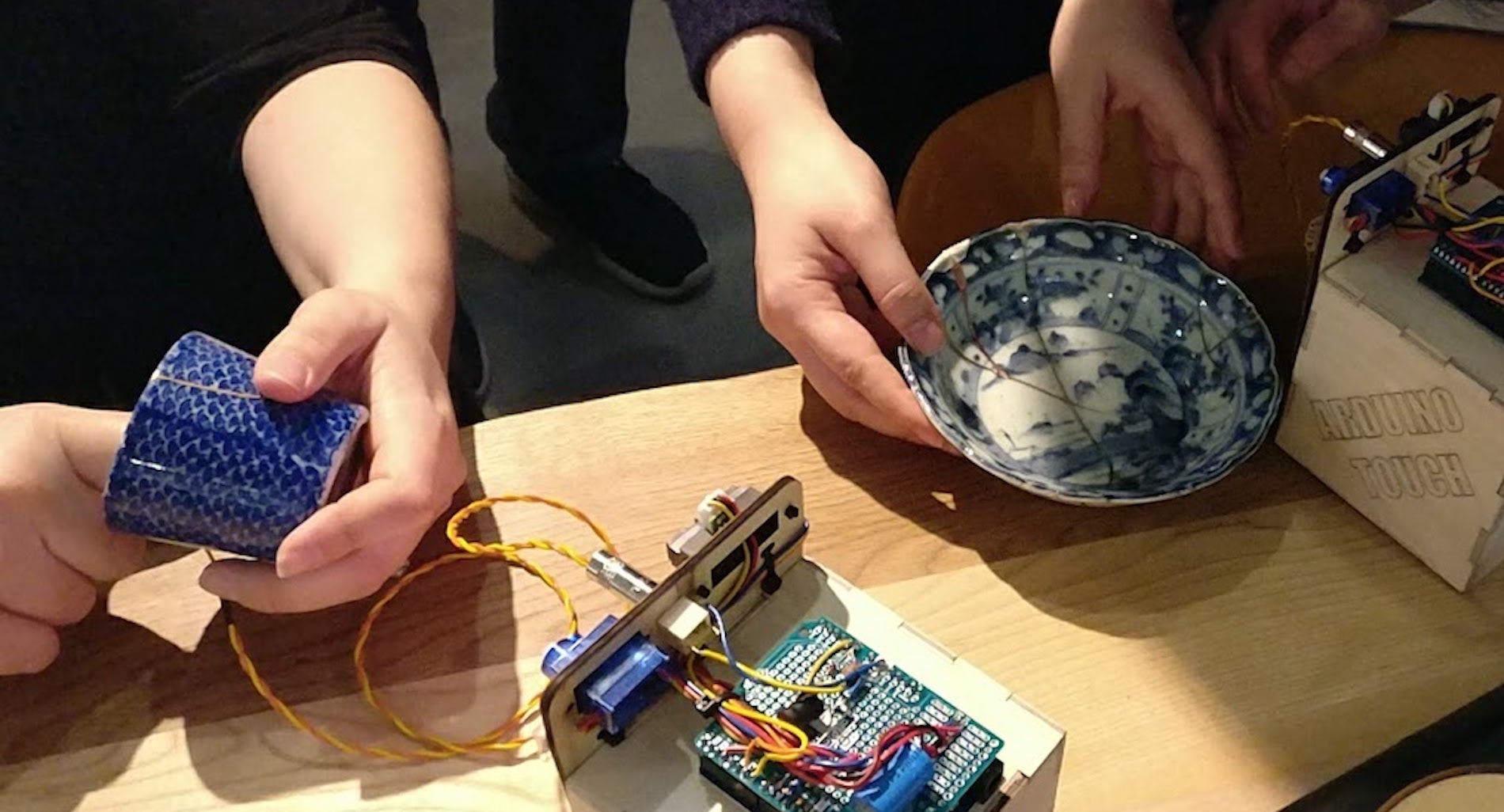

Designing for Meaningfulness is a methodology that advocates for the creation of opportunity in interactions to find purpose, significance and to think critically, and here, the role of friction is ever-present. To find meaningful moments in the everyday, we must be aware that these moments are happening at all – and not just let them pass us by as seamless interactions. According to The Impulse Society: America in the Age of Instant Gratification (2015) by Paul Roberts, our world has become one of convenience, which should allow us this time to reflect and evolve, but instead, our lives become perpetual-motion machines of endless consumption and production, catering again to a late capitalist regime. We crave interaction with others – as was briefly seen in the COVID pandemic, we overcame a distrust or dislike of technology and were spending our days in video meetings, video brainstorms and video cocktail hours or meetups. We seek physical interaction, whether with other people as we discovered when we re-entered the world after lockdown, and also through our growing collective interest in traditional craft and tangible interaction with things we create. From baking sourdough bread to painting, to electronics hacking, people rediscovered a connection to making as well as a shift away from mass consumerism.

When we speak of the problem of designing for wants rather than needs, it is exactly here that Designing for Meaningfulness plays a role; we need to, as a species, understand what we want or need, and why. We have so little time or energy to self-reflect or think critically about what we should or shouldn’t do, or what we’ve been taught to ‘need’. And what we need varies depending on our situation in the world. In many places, the concept of designing for anything beyond survival is not a luxury that all can afford. Whether living in poverty, or in food deserts, or in conflict areas, there are those who have less agency over their lives. It is therefore also the goal of Designing for Meaningfulness to help create opportunities for all to first identify what would be a better life for themselves and then to create that life. A great example of this is in Melinda Gates’ book, “The Moment of Lift” where her team describes how women need safe and reliable access to birth control and how this one change can impact the quality of their own and their families’ lives and even positively impact their communities.

Facing complexity

Another difficulty we face when trying to design for meaningfulness, is that the problems we are facing today are of a complexity and magnitude which is hard to grasp from the viewpoint of the individual designer. We often call these wicked problems, but it is akin to Timothy Morton’s concept of hyperobjects: entities or phenomena, that are extremely vast and complex, and therefore exceed our ability to comprehend them fully. These phenomena have extensive temporal and spatial dimensions making them difficult to grasp within our ordinary modes of perception. Characterized by their nonlocality, they transcend borders, cultures and generations, slipping away from our conscious design, but at the same time weaving a framework we see the world through. Climate change is an example of such a hyperobject, as is capitalism.

So how do we design for better futures for all? Timothy Morton’s answer would be that we should adopt a new way of thinking, embracing the interconnectedness of all things, including ourselves, and recognizing that we are always already immersed in these massive and multifaceted objects. The hope is that by embracing this interconnectedness, we might begin to develop more responsible and sustainable ways of living in a world that is increasingly defined by hyperobjects.

An inherent interconnectedness

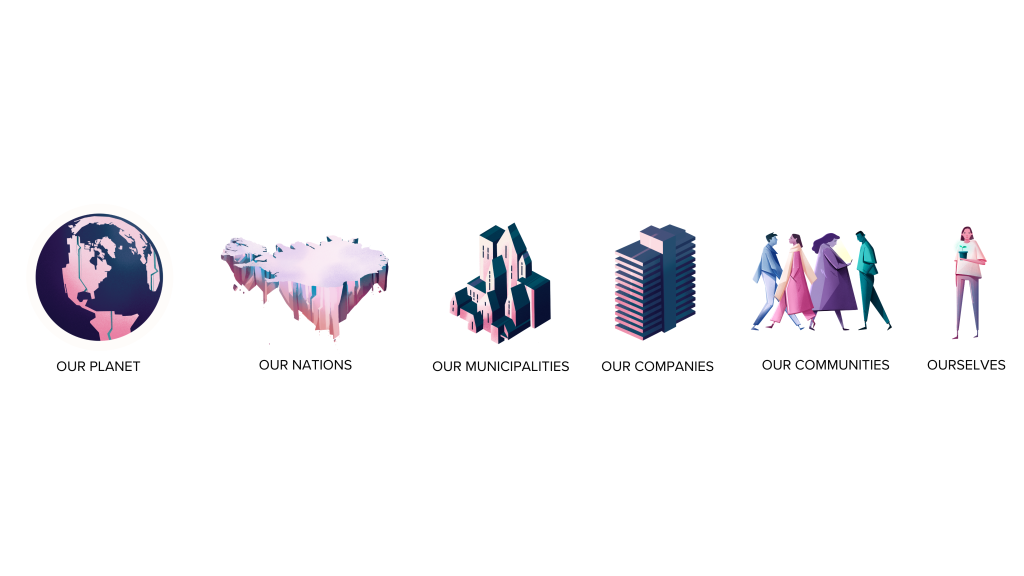

But how do we move away from the individualization of the user-centric approach here? How do we embrace the interconnectedness of all things? Realizing that the world – anywhere, is more than any individual, is the first step. Astrid, a climate change EdTech solution, explains it in 6 Levels: When we speak about climate change, we often speak about the individual – you should fly less, recycle more, drive less, etc. But what about the municipality? The industry? The nation?

In other words, we should practice experiencing the dizzying effect of seeing ourselves immersed in networks and relations with phenomena much bigger than ourselves, designing from points of view of entirely different scales than of the individual. We sometimes experience this effect when we are staring into the night sky and pondering the vastness of the universe, or standing in the shadow of a mountain, formed long before our time. This shifting of scale gives us a feeling of interconnectedness which isn’t exactly empathy, where we feel for, or feel with someone or some situation, but rather it is being moved by an understanding and compassion for a situation or living entity. To consciously design this, we can utilize friction, which helps break our habitual perspectives of our place in the world.

Still too abstract and easier said than done?

We believe it can start with a focus on slowness, meaningfulness, and relations. Designing for slowness is nothing new, but we have failed to implement it – namely because we are too busy. As designers, developers, leaders, thinkers and creatives, we have the opportunity to examine what it is we’re making and raise questions about its role in our lives. So many products today are built for convenience or novelty, designed for immediacy, for instant gratification. What if, instead, we designed for personal development: a sense of identity, purpose, values, and priorities; for moments of significance and transformation; or for critical thinking? With slowness, other things than the immediate wants of the individual are allowed to emerge and come to the foreground.

For too long design has been a way of singling out and siloing users into segments, exemplified by seamless and mindless consumption. Designing for relations between people, and between people and the planet, including non-human entities, does the opposite. It fosters connections, designing for the potentiality of what might arise when we engage in something that is not just a mirroring of ourselves. Allowing us to experience meaningful glimpses of the richness and beauty of the world we are a part of.

We cannot reduce complexity and nor should we design to do so. On the contrary, it is through moments of designed friction that people are invited to grasp a sense of the complex and to reflect on their role and their actions. We can design to help the world slow down, pause, take a breath, and stare into the hyperobject which is our reality and aim to live a meaningful life.

* * *

Vanessa will give a talk at the digital design conference Design Matters 23, which will take place in Copenhagen & Online, on Sep 27-28, 2023. Her talk “Designing for Meaningfulness in future products, services and experiences”, will explore how Designing for Meaningfulness can help us design for better futures. Get your ticket here! And if you want to connect with Vanessa, find her on LinkedIn, Instagram or visit her website.

Connect with Henrik on LinkedIn or visit his website. And if you’re curious about his take on how to understand culture through live encounters with our heritage, read his article on DeMagSign.io Museums: The Hyperinstitutions of the Future.

Cover photo: Electronic Kintsugi – a project exploring Designing for Meaningfulness