There are a multitude of worldviews that go beyond the western-centric mindset. The collective mainstream society in the western world has shifted their attention to mental health, wellness, gender, sexuality, climate change & sustainability, social justice and so on. With this growing movement for change we can try and analyze the designers’ role in all of this; it’s safe to say that designs that are harmful for the planet will be harmful for us all, and the same goes for harmful designs that end up affecting everyone that are made by people that lack the experience and knowledge needed because they don’t reflect the people they’re designing for.

Most often the people who are sitting at the table and making these decisions are rich white men.So how can we design for all living organisms and the planet we cohabit? How can we put these mindsets into actual practices? The question that poses as the elephant in the room is, what is the next step for humanity? How can design help create a new and better future for the planet, humans and our animal relatives?

These are all pretty big philosophical questions, but we believe that it is critical to try and answer them in order for us to evolve as a collective society. Decolonizing Design is a theme we chose to focus on in our Design Matters 22 conference in Copenhagen, which will further nurture dialogue and present individuals who are the catalysts for change. We encourage Ecodesign, Material and Queer Ecology, Indigenous Design, designs that promote more sustainable and inclusive ways of living, but also Future Thinking and Speculative Design.

The topics aren’t new but rephrased in the western world and have become a part of the mainstream conversation again. In this article I want to go deeper into the designer’s role, and my thoughts on initiatives, practices and individuals who are guiding us to change. In addition I want to touch on Indigenous knowledge, tradition and practices that have been overshadowed by capitalism and colonialism. More importantly I want to define the decolonized designer’s role in creating a regenerative, inclusive and community oriented future of design, versus the colonized design thinking and solution oriented scarcity focus which has in turn created harmful designs for our planet and its inhabitants.

Changing the language around design thinking and systems

Earlier this year my partner bought me a book titled Braiding Sweetgrass, Written by Robin Wall Kimmerer, who is a mother, scientist, decorated professor, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. I am in the process of finishing the book but what I have learned so far is that in order to reshape our future we must revitalize and decolonize our language and then our practices.

[Portrait of Robin Wall Kimmerer, provided from website]

Western societies have ignored the teachings passed on to us, the greatest teacher to human life is the world created outside of human capabilities, that has been around long before us. The western centric mythology has focused more on western science studies and ruled out indigienous practices as primitive.

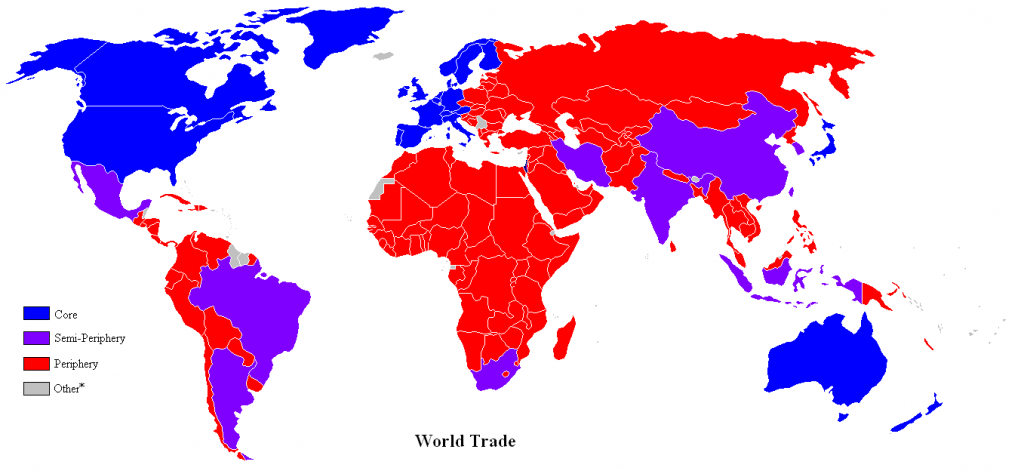

In the contemporary core and semi-periphery of the world we have forgotten language that has a focal point of community versus a hyper individualistic focus taught through capitalism. The World systems theory which has coined the terms contemporary core and semi-periphery, is a post-marxist multidisciplinary approach to world history and social change. It emphasizes the world-system as the primary unit of social analysis.

“Core countries focus on higher skill, capital-intensive production, and the rest of the world focuses on low-skill, labor-intensive production and extraction of raw materials. This constantly reinforces the dominance of the core countries.”

–Wiki

Most of the ugliness and destructiveness in the world today is a creation of humankind. Braiding Sweetgrass reminds people that one of the most important teachings is from our ancestors and relatives which go beyond the human species. Indigineous language and teachings encompass the connection of living organisms and the outdoors. Once we have a relationship with nature, we, in turn, become better human beings. You’re probably asking yourself, how can I as a digital designer incorporate all of this into what I practice and create?

For starters we must go back to the term “design thinking”, which most designers are taught in their profession or academia. For those readers who don’t know.

“Design thinking is a non-linear, iterative process that design teams use to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems, and create innovative solutions to prototype and test.”

– Interaction Design Foundation

This term has done more hindrance than help because we design to recreate or make life more convenient, versus working with what is already present. This is a perfect example of changing the language or narrative we use as humans, and, more importantly, as designers, who help shape the world.

Instead of thinking from a scarcity mindset, we can adapt new terms like “Indigenuity”-a description coined by Daniel R. Wildcat, a Yuchi member of the Muscogee nation of Oklahoma, Ph.D, educator, author and so much more. Indigenuity (Indigenous ingenuity) acts as a practice that was created to solve contemporary problems.

[Portrait of Daniel R. Wildcat Courtesy of Museum of Native American History]

“Indigenuity is the result of a people’s long intergenerational transmissions of experiential knowledge over millennia resulting… Indigenuity frames solutions in terms beyond singular fixation on rights and counterbalances those concerns with a recognition of inalienable responsibilities humankind has to our plant, animal and other natural relatives with whom we share this planet.”

– Museum of Native American History

What we can learn from Indigenuity is to further separate ourselves from a design thinking mindset, based on data and variables, and incorporate indigenous practices and people into this process. In order to live in a more mindful and empathetic way we need to understand the symbiosis between us and our ecosystem, which is earth.

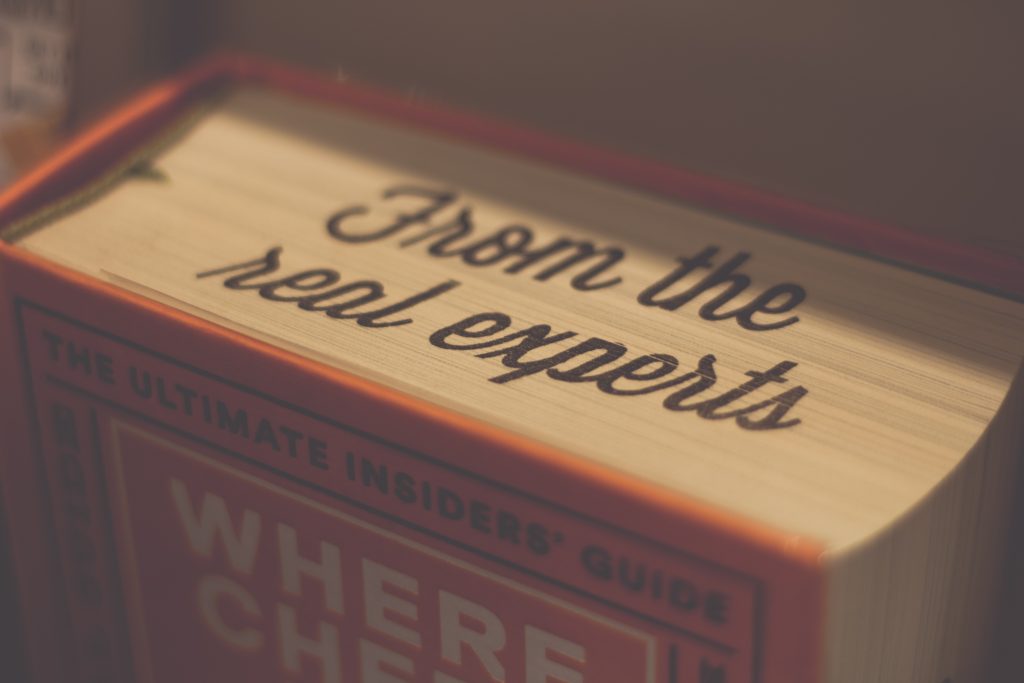

Indigenous people were the original modern day scientists and engineers through thousands of years of observation and experimentation. Increasing Indigenuity in our practices and language helps combine indigenous wisdom and modern science. The contemporary world has a huge emphasis on where authority and knowledge come from and invest all of their trust in human “experts”, controlling variables and answering the question, how does it work? Which often only answer true / false questions.

Moving Forward, who are the experts?

To move forward we should think critically about who we deem experts in the contemporary core world. We can take some things from western science which reject ancient practices but not observations and experiments, and realize that indigenous experts through years of testing, observation and experimentation were already practicing these deductive methods long before the rationalism movement.

Rationalism relies on the idea that reality has a rational structure, where mathematical and logical principles are more esteemed than sensory experience.Data can be important when developing a prototype, but it is also important to redefine the meaning of ‘expert’ and to incorporate ancient practices,traditional knowledge, and indigenuity into our processes.

Because the western centric Imperialist mindset has colonized the world, we have thought about the world from a scientific exploitative point of view, where colonizers exploited indigienous peoples raw materials and used slave labor and traditional knowledge for the industrialization of argiculutre, somewhere along the way with capitalism it further became about mass production that’s cheaply done in the quickest way possible.

Which looks from a thought process of manufactured scarcity, extractive economies and capitalism. Somehow we have all been led to believe this lie that there isn’t enough teachings and knowledge from ancient indineous wisdom that can be applied to modern day science, and that the theories coming from western science are more valuable than technologies and teachings that were around before we even created the idea of western science.

A lot of these ideas and realizations are from a recorded discussion with Daniel R. Wildcat and Robin Wall Kimmerer about the book Braiding Sweetgrass for the Museum of Native American History, One of the valuable lessons I learned from this recorded talk is that, even with the ugliness in the world today we must never forget the beauty of the indigenous practices, the beauty that is water, air, fire, plants, animal relatives and so much more. The creativity and brilliance of plants and our animal relatives, the beauty of the outdoors is medicine for the human soul, beauty refers to taking in what is around us which acts as a guide or teacher in life. Beauty can be seen everywhere in people and our ideas, philosophical tradition which mirrors the symmetry of the world.

Straying away from human centered design.

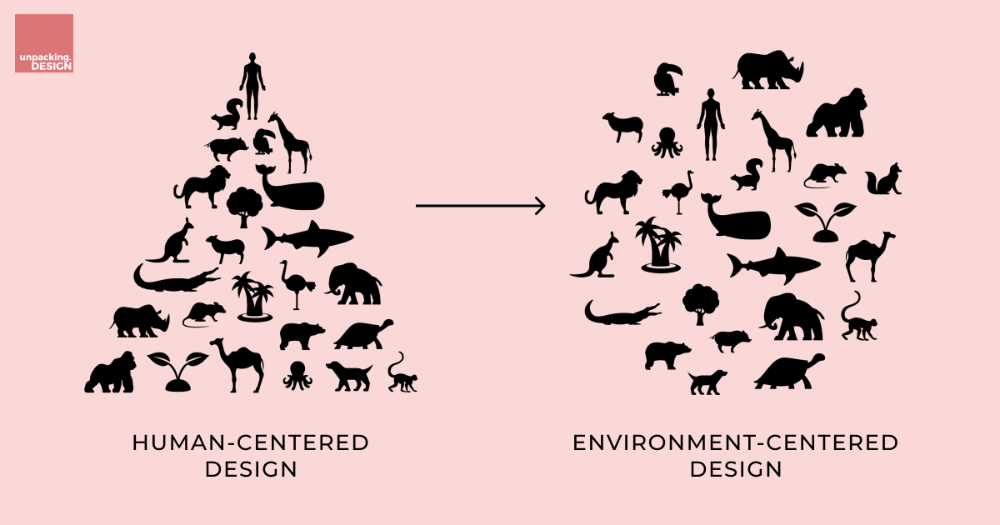

What is human centered design? human centered design derived from a standard of steps from user research and observation, ideation and iterative prototyping. This process is repeatable and is the framework for “design thinking”. This repeatable process has a huge margin of error which is that it only focuses on human beings versus the bigger picture that is simply the fact that humans are a small minority amongst many other living species here on earth. We are a part of nature and play a role just like the microbes surrounding us and the mycelium networks underneath the soil.

How do we stray away from designing from a western mythology that is so centered around the individual human experience at this moment in time and design for future generations? That is the mindset that designers and humankind needs to adopt. When we eliminate the focus on individualism and start thinking of collectivism, in turn we will produce better designs.

Julia Watson is a landscape designer and educator and author of Lo-TEK design radical indigenism. Lo-TEK reframes local technologies and their communities as an evolutionary extension of ife in a symbiosis with nature. Lo-TEK stands for Local + TEK- traditional ecological knowledge. Lo-TEK, like Braiding Sweetgrass, discusses the symbiotic relationship between us and nature. Instead of the “Survival of the symbiotic” in contrast versus in compliment. Lo-TEK uncovers what we consider as technology in the western world. In response to fire, sea level rise, etc. conserving global biodiversity and the correlation between loss of biodiversity and loss of culture.

The book puts a spotlight on communities where technology is redefined from the western perspective: technology can use nature and can be considered nature. The Bengalis of India in Kolkata have 300 fish farms which reuse waste water and create a system that cleans the city’s sewage for free, the community sits on the edges of the Kolkata wetlands. As the population grows so does the city and in turn the waste water. This symbiotic use of fish and wastewater combats the increase of waste water.

Another community highlighted in the book is located in the southern wetlands in Iraq where the Tigris and the Euphrates river connect. For 6,000 years the Ma‘dān have lived on floating villages, on human made islands that are constructed from a single species of reed. The Qasab reed has multiple purposes where it provides flour for humans, food for animals, and material for building. There are so many techniques and processes to use from the past and civilizations that haven’t fully adopted the western industrial revolution.

There has been a suppression of Indigenuity since the Colonial era and Industrial age. A perfect example is the use of fire. From a western perspective, fire was thought of as destructive. When in the past fire was used as a prescribed burn to generate biodiversity and protect the land from catastrophic fire.

The Digital Designers role

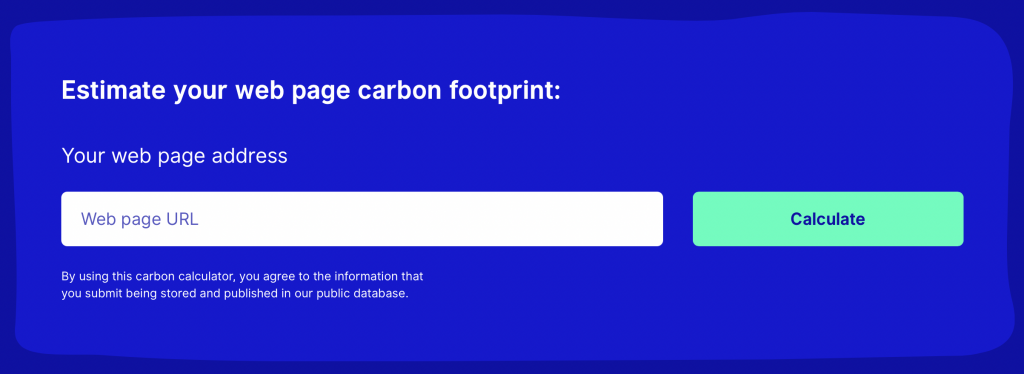

We have talked a lot about design itself, but what about digital design? How does this fit into the equation, and how can we apply these examples from nature? Well, computers use a huge amount of carbon, and as we further integrate the digital world into our lives, we need more energy to power this. The website carbon tracks the amount of carbon used by a website, it’s pretty scary to see the amount a single website generates.

“The internet consumes a lot of electricity. 416.2TWh per year to be precise. To give you some perspective, that’s more than the entire United Kingdom. From data centres to transmission networks to the devices that we hold in our hands, it is all consuming electricity, and in turn producing carbon emissions.”

–Website Carbon

Now with the rise of crypto currency and NFTs, and a plethora of apps designed for your everyday need, we’re continuing to integrate every aspect of our life in the digital world. Digital designers now more than ever need to rethink and shift their focus to create better decolonized designs, more importantly further nurture allyship towards indigenous communities and design. We need all of the design communities to create this future that we want. Of course designers can’t do this alone, we also need large corporations to sponsor indigenous communities.

We’ve uncovered a lot of heavy topics, it’s okay to feel overwhelmed and still unsure of where to start. As highlighted above, the first step is to change our language, which, in turn, changes our thought process and then our practices. At our Copenhagen conference in September of 2022 we hope to further deconstruct and decolonize the current dogma in design systems, and showcase the dichotomy between modern science and indigenous practices. The desire and need for dramatic change in our belief system is already present, it’s time we start working together with nature, and the marginalized QTBIPOC (Queer, Trans, Black, Indigenous, People of Color) communities who need to be included in the design process.