Tobias Røder is a self-taught, independent graphic designer and an international design teacher. He is the manager of Studio Tobias Røder, a Design Studio based in Copenhagen that creates visual identities for the private and the public sectors. He is indeed the creator of stand-out identity designs for the Danish Government, Tuborg, and Lars von Trier. He also designed the logo for Design Matters.

In an industry that tends to ‘wrap things up’ — in patterns, colors, shapes, and effects — Tobias likes to deconstruct. In fact, his works are often labeled as minimalist, iconic, or even provocatively simple. The focus of his design work is to create something that communicates effectively the identity of the projects his clients commission. Design, in this case, is not a mere form of art anymore; it becomes a medium to send a message to the world.

In fact, what we are progressively seeing is designers abandoning the sole role of service providers to embrace the role of design activists too. Activist designers are thinkers who are aware of the environment that surrounds them and react or fight for their cause through design.

What obstacles do activist designers face when they try to fight or raise attention around social, political, and environmental problems? We met with Tobias to comprehend his standpoint on activism used in design work.

My job is basically to help get people’s attention. And the way to do that is by making things stand out. That’s nothing new. We’re constantly being bombarded by messages from all sides, at all times, and our collective span of attention seems to be decreasing. Today, people’s attention is a valuable commodity, and the very business model of global tech giants.

Attention works by focusing on one thing at the expense of other things. But it’s hard to focus when everybody is screaming for your attention. So I worry that the battle for people’s attention will backfire, making it even more difficult for us to focus, as a society. That’s the only change, really. Obviously, we have gotten some new tools too, but the basic purpose of our craft, as I see it, remains the same: to design things that get people’s attention.

To me, design is a tool. So it will never be the designer’s role to come up with a political strategy, or to launch a new form of behavior, for example. That’s the role of a spin doctor, perhaps, but not of a craftsman.

My job is to craft the design around the idea that my client wants to communicate. Maybe that’s why I find that we sometimes spend too much time talking about design when, really, what we should be talking about are ideas.

Do you see any challenges in being an “activist designer”?

I know what an activist is, and I know what a designer is. But activist designer, at least for me, is quite new. I’m not sure I know the exact meaning of this term. Sometimes people add the word designer to a noun or the name of a product, because their purpose is to make that thing more interesting or appealing. Think about advertisers sticking “designer” in front of “kitchen” or “vacuum cleaner”, for example. Why do they do that? Probably to make that object appear something more than it would be in and of itself.

So, my concern is that using the title activist designer, in my view, might create the illusion of giving an extra value that might not always be there. This might be perceived as untrustworthy or decptive. And designers should be aware of this.

If someone actually decides to be an “activist designer”, I think one of the biggest challenges will be to be taken seriously. They will have a credibility problem, I think. Also, how would they sustain themselves? Activism, by definition, is the fight for a cause, not a craft for profit. So I think the “activist designer” is in for a hard time in more ways than one.

Where do you think the credibility problem lies?

Because I’m not sure about how an activist designer is defined, I will take a critical stance to this question.

The problem lies in the fact that the concept of “design” is sometimes being used at random, in my opinion. In fact, corporations have found that if they name their products something with “design”, they can double the price. Design is everywhere, because it creates added value. The drawback is that the concept of design is being watered down, losing its meaning. We’re starting to see people deliberately deselecting products named anything with design, because they’ve seen through the underlying strategy. The product feels phoney. And so I would recommend the so-called activist designers to call themselves by a different name. Such as simply activist or designer.

Can a designer be designing for a cause, instead of only for profit? Do you think the two things could be together at all?

I got my first real job as a graphic designer at the age of 18. One day as I was coming home from work, and ran into a group of people protesting. They were wearing balaclavas, brandishing badly drawn signs saying “Shell go to hell”. I was working for Shell at the time. One of the protesters spotted me and came over to me. It was my little sister. She was always the “activist” in our family, and I was always the “designer”.

Today, I have 30 years of experience as a graphic designer. I’ve grown wiser about myself and the world around me. There are clients I no longer work with, even if they offer an exorbitant amount of money. On the other hand, I just finished working on a project with Danish poster artist Per Arnoldi that he and I did for New York Climate Week. For free.

I’m happy to work for a good cause. Our climate, for instance. I don’t need to make money doing that. But I know that that means I’ll have to ramp up the pace on my other projects. To be able to pay the bills, you know.

In a final analysis, it must be what I do that defines who I am. Not what I call myself.

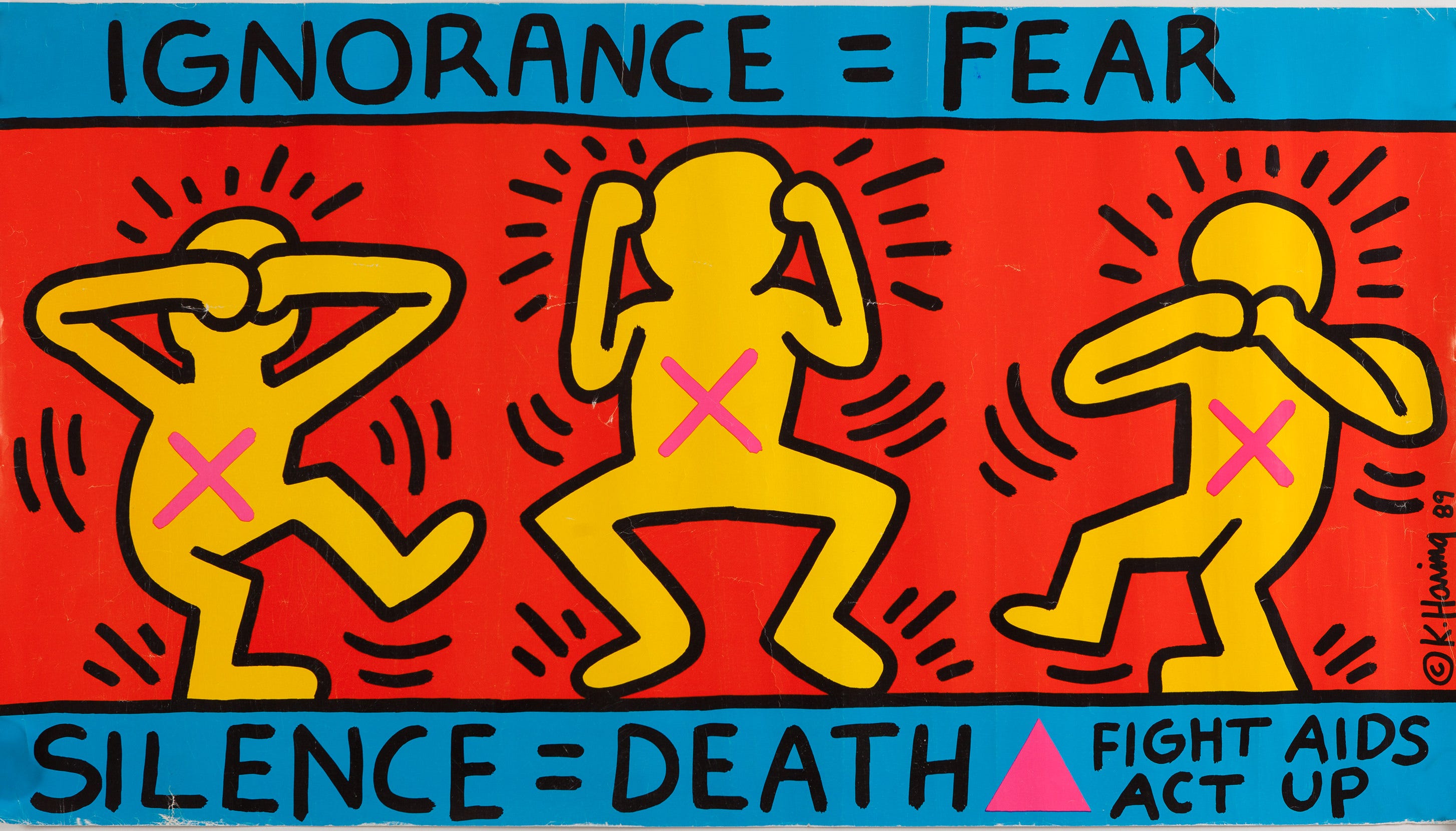

I admire the graffiti artist Keith Haring. In the 1980s, he was one of the first people to bridge the gap between vandalism and established art, using the N.Y. subway, among other things, to spread visual responses to such dark issues as the nuclear threat, racism, homophobia, drug addiction, and AIDS. His iconic graffiti dog was sold as merchandise, and he attracted a non-art crowd — “kids from the Bronx”, as he called them — to a world they probably wouldn’t otherwise have found interesting. But here’s the thing: Keith Haring was an artist, not a designer. He wasn’t handed a brief by a client. He suffered from AIDS and felt a very personal need to bring attention to the issue.

What is the most important thing designers need to think about when designing new products?

We should ask ourselves “do we need it?”, “does it make a positive difference in people’s lives?”, “is it reusable or degradable?”.

What are your thoughts on how activism can be included in design?

Design should activate. That’s the purpose of design: to spark an action, to get people to do something. Sometimes, this can be a change in behavior. Design can thrill us, make us see things differently, and start something. That’s why “activism” or “to activate” works naturally with “design”.

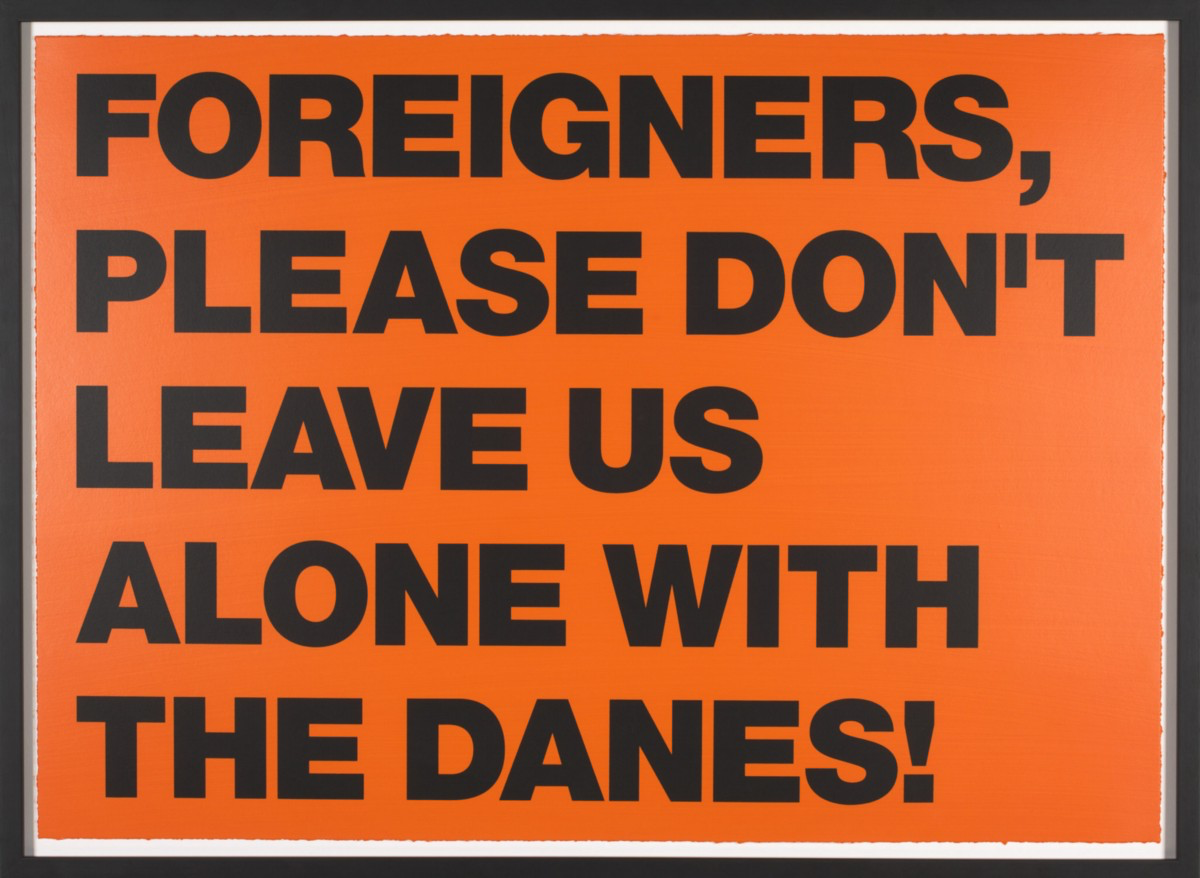

One example of activism in design that I can think of is this: in 2002, posters with the wording Foreigners, please don’t leave us alone with the Danes were put up in the streets as a comment on the increasingly harsh climate in Denmark with regard to public debate on immigrants and issues on integration.

This was the work of three activists who teamed up with a designer to get their message across. It wasn’t the work of an activist designer. But it was a nice case of design meeting activism, and of using humor to push people’s thinking on a certain issue. Today, 17 years later, you can still see that poster. But now it hangs in people’s living rooms, framed.